Stephanie Margaritidis | Interior Designer / Educator / Artist

Yiayia’s Sunday

My grandmother Artemisa—with her ancient name, fitting for a woman of her presence—died on a Sunday. To me, she was always Yiayia. Her face held dignity; her spirit, a quiet defiance and in her embrace, there was comfort during childhood nightmares. She was always ‘old’ in my eyes, though at just 55, she and my Pappou had arrived in Australia during a blistering November heatwave, leaving behind a life steeped in black-and-white for the Polaroid sun of a new world.

In our Greek family, death was no stranger. It sat with us at the kitchen table, stirred into our coffee, talked about as casually as the news. The rituals, the grief, the mystery of the afterlife—it was all part of our staple.

My grandparents slept under the watchful eye of a large Orthodox icon—a looming tapestry of Heaven and Hell that reminded me of an El Greco, but with the haunting precision of a Hieronymus Bosch.

That icon takes me back to the island of my birth, to the orchard where my earliest memories of death live and where in its verdant life, I hid in a swinging hammock avoiding summer siestas with Yiayia as my accomplice. Church bells would toll through the portside, announcing another boy-man lost to the sea in the island’s treacherous sponge trade.

In Greek tradition, death is not hidden or hushed. It is lamented—loudly, openly, and with reverence. Black clothes, wailing women, food offerings, the lighting of candles. Mourning is ceremonial.

The gravesite becomes a threshold—a sacred intermundium—where we whisper, "Αἰωνία ἡ μνήμη" (eternal be their memory). I’ve always loved cemeteries, stone markers speaking across time, telling us who once was and who still is.

The week before Yiayia died, she became tomb-like in her nursing home bed. Her eyes remained closed, but her mouth spoke—again and again she called her mother’s and sister’s names with a strange urgency. It was as though she was already elsewhere, cloaked in a thin veil between this world and the next.

I visited daily, hoping to rouse her, hoping to pull her back. Her breath rattled through a narrowing trachea. What did she see behind those lids that now refused the world? Was she already with them?

Midweek, she opened one eye, locked it onto me. “My ancestors have called me,” she said. “They will take me with them on Sunday.” She asked that all her children, grandchildren, neighbours, and friends come visit. A final gathering. A farewell. I remember holding her hand telling her that she wasn’t going to die more for my sake than hers.

That Sunday, we gathered—the whole Greek clan. Solemn silence and tears collided in that small room, stories held tightly behind clasped hands and red eyes. I lay beside her, holding her wrist, feeling the faint thread of her pulse. She opened one eye again, scanned the room, and asked, “Is everyone here?”

“Yes, Yiayia. Everyone’s here.”

And with that, her pulse began to fade. I waited, not ready to say the words out loud. Not until my aunty asked, “Is she still alive?”

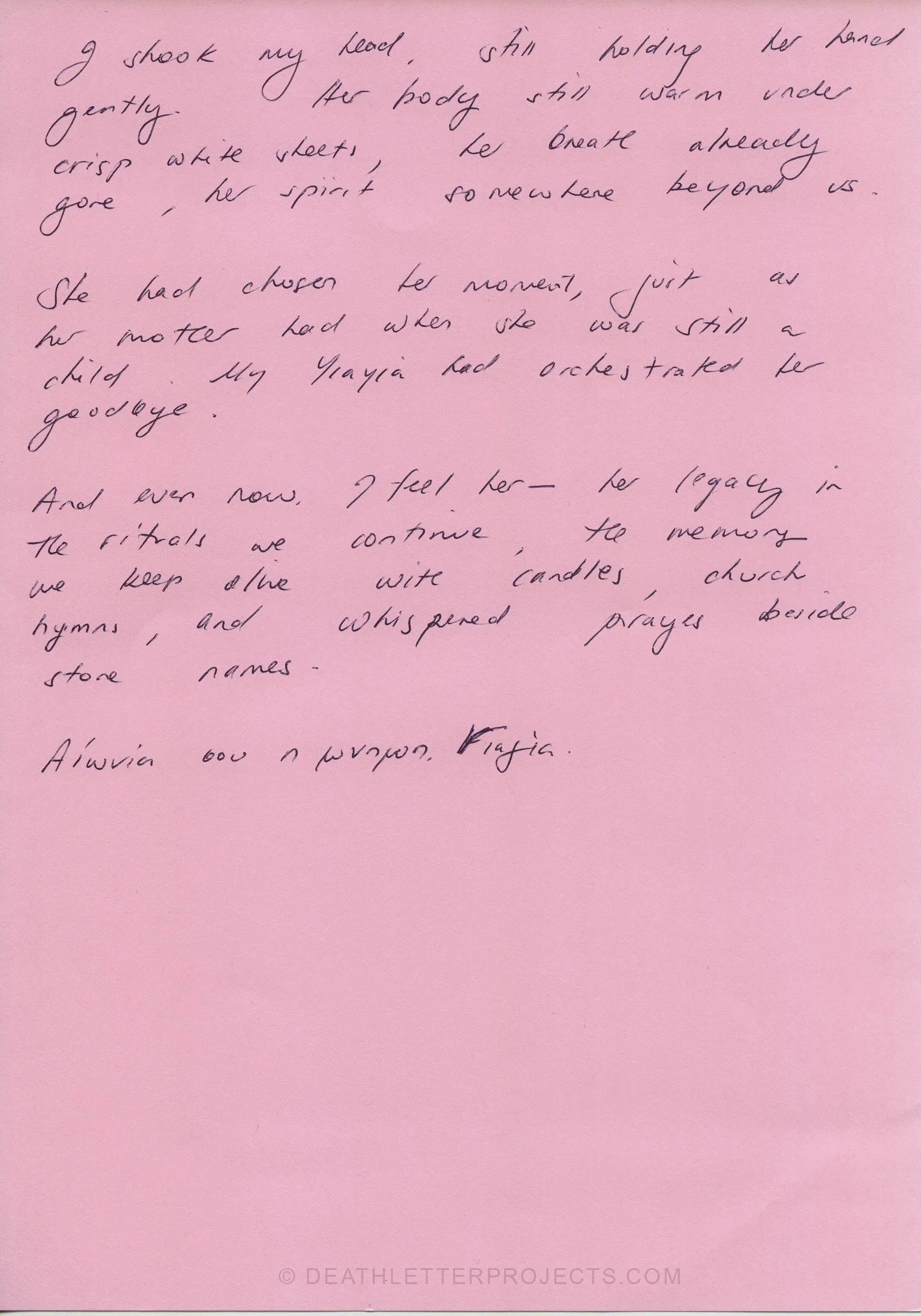

I shook my head, still holding her hand gently. Her body still warm under the crisp white sheet, her breath already gone, her spirit somewhere beyond us.

She had chosen her moment, just as her mother had when she was still a child. My Yiayia had orchestrated her goodbye.

And even now, I feel her—her legacy in the rituals we continue, the memory we keep alive with candles, church hymns, and whispered prayers beside stone names.

Αἰωνία σου ἡ μνήμη, Γιαγιά.

[May your memory be eternal, Grandma]

—Stephanie Margaritidis (2025)

Editor’s note: Stephanie is an interior designer, decorator, stylist, educator and artist whose childhood in the Aegean, formed her design ethos of expressive eclecticism. Her home in Sydney’s Inner West, which she shares with her partner, sculptor Adam Laerkesen and son, Matteo has been featured in Vogue Living and leading publications. Further into: www.studiomargarit.com.au

The Death Letter Project welcomes your comments and feedback. Please feel free to leave a comment on our Facebook page or alternatively submit a message below.